Replicating the tomb of Tutankhamen: Conservation and sustainable tourism in the Valley of the Kings

Introduction

|

| Figure 1. Painted burial chamber in the tomb of Tutankhamun |

The principal themes touched upon in this article are heritage management, conservation and sustainable tourism. Conservation is the science and art of preventing further degeneration and achieving stable conditions by means of monitoring devices and physical techniques that should, in theory, be fully reversible. The degree to which conservation activities are successful depends on a number of factors, and in Egypt one of the most important of these is the need to balance the vulnerabilities of sites with the interests of tourists and the economic need for the income generated by tourism. Sustainable tourism, the term used to describe this balancing act, is particularly difficult to achieve where tourist demand for a site is high, and tourist revenue generated by that site is a vital component of a state or local economy. In Egypt, the Valley of the Kings contributes to both the state and local economies, generating revenue and providing employment in all areas of the tourist sector.

KV62 sign in the Valley of the Kings

|

| Figure 2. KV62 sign in the Valley of the Kings |

Background

|

| Figure 3. KV62 at the time of its discovery, photographed by Harry Burton |

“The authorities face agonizing decisions. Do they admit visitors to royal graves and witness the near-certain deterioration and perhaps disappearance of unique wall paintings from sheer people pressure? Or do they close everything to save it for future generations? . . . The dilemma pits the preservation of the priceless and finite archive that is ancient Egypt against the pressing economic needs of a developing country – altruism for future generations against short-term advantages” (Fagan 2004, p. 252).

In 2008 the Getty Conservation Institute was appointed to work with the Supreme Council of Antiquities to examine the current condition of the tomb and develop an ongoing programme of conservation for it; and in 2009 both the Getty Conservation Institute and Factum Arte, the company responsible for the facsimile of the tomb of Tutankhamen, carried out detailed surveys of the tomb.

Long term plans to close KV62 to the general public, to protect it against the damage inflicted on it by the volume of tourists that visit annually, are now in doubt, but it is thought that the tomb cannot stay open indefinitely. Estimates of the closure date vary, but it is probable that it will be closed in the next few years. The facsimile, now completed, but not yet available to the public, would enable visitors to experience unprecedented access to an exact copy of the original tomb, allowing the 3000 year old original to be conserved and preserved for the future, with the risks of damage significantly reduced.

Humidity, dust and vibration

|

| Figure 4. Tourists in the Valley of the Kings |

Even with current restrictions to the number of visitors permitted to enter the tomb, which limit them to 1000 a day, problems are caused by the humidity of human breath, fluctuating heat, organisms brought in on tourists’ clothing, the ongoing vibration from tourist feet and large volumes of sand-filled abrasive dust, which is impossible to remove without damaging paintwork and plaster. The diesel trains introduced several years ago to ferry tourists from the car park at the end of the road that leads to the Valley of the Kings add noise, fumes and oil into the mix, polluting the atmosphere. Combined, these problems are undermining the attachment of paint to plaster and plaster to the rock-cut walls. According to the Theban Mapping Project’s The Valley of the Kings Site Management Masterplan, during the height of the 2004 season the Valley of the Kings received 7000 visitors per day and over 1.8 million visitors in total for that year, and before the Egyptian revolution, the Site Management Plan operated on the assumption that the current rate of 7,000 visitors per day in the Valley of the Kings would potentially reach 15,000-20,000 per day by 2014.

In the Eighteenth Century Joachim Winckelmann proposed that sites and artefacts should be conserved and preserved, not restored, renovated or reconstructed, a view shared by most heritage professionals today. Winckelmann’s proposed approach was formalized much later in a number of charters, including the 1964 International Charter to the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites, other wise known as the Venice Charter. Other charters, available in full on the ICOMOS website, also make recommendations and offer guidelines to support conservation and heritage management. The need for conservation in Egypt was already recognized in the early 1900s by Flinders Petrie, James Breasted and others, and in his excavations of Tutankhamen’s tomb, Howard Carter was already bemoaning the impacts of humidity and dust brought into the tomb by visitors. Egypt has, sporadically, followed some of the guidelines, but conservationist Michael Jones of the American Research Centre In Egypt lists some of the more distressing examples of damage to and losses of heritage, together with the causes, in his chapter in Wilkinson’s Egypt Today. He cites tourism as “one of the main threats to the survival and authenticity of many Pharaonic monuments,” a difficult threat to challenge due to the importance of tourism to the economy. In 2005, for example, Egypt earned 6.4 billion US dollars in tourist revenue, providing work for around 12 per cent of the nation’s workforce.

|

| Figure 5. Three-tombs ticket, Valley of the Kings |

An article by McLane and Wüst in 2000 describes how, in the late 1990s, the American Research Centre in Egypt (ARCE) was commissioned to take steps to prevent damage from flash-floods to the tombs of Ramesses I and Seti I by lowering the ground level in front of the entrances and providing them with protective walls and steps. In 1986 the Getty Conservation Institute was appointed to carry out extensive conservation work in the tomb of Nefertari in the Valley of the Queens, one of the most beautiful of all the West Bank tombs, work that was completed in 1992. The Getty Conservation Institute is now carrying out a conservation assessment of the rest of the Valley of the Queens. In 2006 Kent Weeks and Nigel Hetherington submitted a site management plan for the World Monuments Fund, making recommendations for restricting visitor numbers to the Valley of the Kings, introducing air flow systems, replacing glass panels with Plexiglass and monitoring temperature humidity to permit the estimation of the number of tourists that should have access to each tomb.

In spite of these various initiatives, Michael Jones is pessimistic about the future of the royal tombs (2008, p.118):

“At the moment, the improvements to the infrastructure and the measures taken to protect the tombs lag so far behind the ever-increasing tourist numbers and international cultural heritage management practices that it is difficult to see how tombs will survive.”

He suggests that “[T]he ultimate solution may be replicas.”

Assessing the Condition of KV62

|

Figure 6. “Art and Eternity,” one of the two books about the conservation of the tomb of Nefertari |

The threats to the tomb of Tutankhamen were once again raised in 2008, when the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) was appointed by the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) to carry out a conservation assessment project at the tomb of Tutankhamen, over a five year period. The GCI have worked with the SCA before on various projects, including the conservation of the tomb of Nefertari in the Valley of the Queens in the 1980s, the development of oxygen-free cabinets for the Royal Mummies collection in the Cairo Museum and an environmental study of the Great Sphinx at Giza. At the same time, Factum Arte, funded mainly by the Factum Foundation, began work on its facsimile of the tomb of Tutankhamen.

Prior to the GCI’s involvement, a number of measures were taken to attempt to both preserve the tomb and keep it open to tourists. Already recognized as a conservation problem in the 1980s, the tomb’s painted walls were coated with an acrylic-based substance, both to stabilize their current condition and allow the tomb to remain open to the public. The well-intentioned efforts, completely irreversible, merely exacerbated the existing problems. The impermeable layer, trapping salts, other minerals and water beneath it, caused the substances to leach from the rock into the rock plaster, forcing it from the walls of the tomb. During the Factum Arte survey of the tomb the team found that even earlier attempts had been made to reverse the damage, including refilling and repainting, thereby substantially disrupting the integrity of the original.

The GCI’s project is being rolled out in three phases, complying with international guidelines stating that the first stage of conservation should be recording and documentation. During the first phase, the GCI have been assessing the history and condition of the tomb, measuring current conditions against the original Harry Burton photographs from 1922, forming diagnoses of the deterioration of the wall paintings and suggesting solutions to prevent ongoing decay. The environmental monitoring, which began in 2009, includes assessments of exterior and interior conditions, including humidity, temperature, atmospheric particles, carbon dioxide and air exchange. In the second and third phases, rolling out simultaneously, the intention is to implement the conservation plan, establish long-term monitoring systems and train SCA conservators. The results of the project will then be evaluated and disseminated.

|

| Figure 7. Brown spots disfiguring the burial chamber. |

Part of the Getty’s remit was to assess the brown spots that disfigure the paintings in the burial chamber and appear on the walls of the other rooms as well. It was speculated that the spots might have been the formed when the tomb was opened in 1922 (taken some time after the tomb opened) were present when the tomb opened. Microbiologist Ralph Mitchell from the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, together with chemists from the GCI, inspected the spots and, using molecular analysis and DNA sequencing, found melanins, which are a by-product of fungal activity. Mitchell believes that the spots were produced by sealing wet paint in the tomb with the mummified body, food offerings and possibly incense, which would have favoured microbial development. The lack of micro-bacteria on the unpainted ceiling tends to confirm this. The implication is that the tomb was both prepared and sealed in a hurry. The micro-organisms have invaded both paint and plaster to the molecular level, meaning that the damage is irreversible. Fortunately, the organisms that created the marks are no longer active, and therefore pose no ongoing threat.

In January 2011 Zahi Hawass, then secretary-general of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, announced that the tomb would soon have to closed for its own protection. Shortly after that, the Arab Spring revolution saw a change of leadership in Egypt, and Hawass lost his job shortly afterwards. Until now the tomb has remained open and a solution that balances the needs of tourism, the economy and the tomb itself has not been implemented, and the sad truth expressed by Michael Jones is that, “no amount of conservation of restoration can halt decay; it can only slow it down” (2008, p.99). However, the completion of the facsimile by private company Factum Arte, suggests that a solution is at hand.

The value of facsimiles

Before going through some of the objections to facsimiles, it is worth considering why facsimiles are thought to have advantages. There are five main benefits to the creation of a 1:1 facsimile of any site:

- A facsimile is an exact copy, not an approximation of the original, or a part of the original

- It offers the ability to conserve and prevent further degradation of the original site

- It offers the ability to record the original state of the site, together with any previously Unrecorded and unobserved details

- It has the potential to provide an equivalent experience for tourists and the associated income derived from those visitors to ensure their ongoing involvement, education and pleasure

- It may offer ongoing or additional employment for local residents

|

| Figure 8. Lascaux |

The Palaeolithic cave system of Lascaux, in the Dordogne, is an elaborate network of chambers and corridors that are justifiably famous for their marvellous paintings. Discovered in 1940, Lascaux became a popular post-war tourist attraction, with visitors arriving in ever-increasing numbers to see the stunning art work for themselves. Within the space of two decades the images began to suffer and the difficult decision was taken to close the tomb to the general public, to be replaced eventually with a replica of part of the cave. The replica, named Lascaux II, opened in 1983, eleven years after the closure of the original, after a decade of work. There were concerns that the copy would not attract the same volume of visitors, but although it inspired much debate about whether a copy could replace an authentic experience, Lascaux II continues to be very successful. Building on this success, five parts of the cave not included in Lascaux II have been reproduced and are being exhibited first in Bordeaux, France, before travelling first to the USA and Canada and then Asia on a tour that will not see the exhibition returning to France until 2020.

|

| Figure 9. Altamira |

A rather different proposition is the touring exhibition Tutankhamun: His Tomb and Treasures, a specially commissioned display of over 1000 replicas of objects from the tomb of Tutankhamen, including the famous golden mask and three of the four golden shrines. As there have been touring exhibitions featuring original items from the tomb, the value of an exhibition of replicas could well be questioned. In fact, the exhibitions featuring original items from the tomb, most notably Tutankhamen and the Golden Age of Pharaohs and Tutankhamen, The Golden Beyond have visited only a small number of European destinations, one Australian destination, and have been touring mainly in the U.S. The Egyptian authorities have stated that when the items return to Egypt, there will be no more travelling exhibitions. Access to the original objects has therefore been limited.

In the future, for those who are unable to visit the exhibitions but wish to see items from the tomb, a visit to Egypt will be necessary. As this is not a practical proposition for everyone, the idea of exhibitions of replicas may well be the answer. Although they don’t have the same “wow” factor that the original item may generate, the items have an impact of their own. Jaromir Malek, former Keeper of the Archive of the Griffith Institute, was dubious about the benefits of such an exhibition before he went to visit it himself, asking the question “Can there be any advantages in exhibiting mere replicas of objects found by Carter and Carnarvon in Tutankhamen’s tomb” (2009, p.2). But he concludes that whilst it is not the same, missing that certain “frisson” that an encounter with the original objects will provide, the exhibition certainly has real benefits. First, items that will never leave Egypt again and are not present in the current exhibitions of original items are included. Second, they can be manhandled and displayed in a way that the originals could never be, meaning that highly imaginative displays can be arranged which in the case of this exhibition includes a display, in a smaller-than-life tomb replica of how the valuable items were deposited in a haphazard fashion in each of the chambers. Finally, the emphasis is not on creating blockbuster impact, but on information and education using fresh and imaginative devices to involve the visitor. Malek concludes: “So, somewhat reluctantly, from being a sceptic I have become a convert. This exhibition can do things which no other, perhaps with the exception of future virtual reality shows, is able to do.”

Both the Lascaux and Altamira projects demonstrate how economic, visitor and heritage needs can be balanced. Both are success stories in terms of visitor satisfaction, sustainable tourism, heritage management and local employment, providing a useful model for other projects faced with similar dilemmas. In both cases, ticket sales continue to contribute to conservation work in the Palaeolithic caves. Similarly, the exhibition of replicas, Tutankhamun: His Tomb and Treasures, received 30,000 visitors a day in its first venue in Brno in the Czech Republic and has since attracted over 3 million at other venues.

The Tutankhamen facsimile

|

| Figure 10. The Factum Arte facsimile of the KV62 burial chamber |

|

| Figure 11. The Factum Arte facsimile of the tomb of Tuthmosis III |

Although the burial chamber is the only one of the chamber to be reproduced, the facsimile has been provided with a short ramp, echoing the original, and an antechamber which will provide visitors with the sense of passing from the outdoors into the interior of the tomb.

As with the Getty’s project, the Factum Arte plan conforms to the basic tenets of conservation, and began with a phase of recording and documentation. The data was collected during 2009 over a six week period, during which around 1000 visitors a day were still visiting the tomb and asking a myriad of questions, and then a further three years were taken to complete the facsimile. The photographic data has been supplied to the Getty Conservation Institute to assist with the completion of their report, and for the purposes both of comparing the tomb’s state in the past and allowing monitoring of how it changes in the future.

|

| Figure 12. Damage to the original paintings in KV62 |

The GCI have to take these earlier attempts to repair and preserve the tomb into their conservation plans. The intention is for the conservation and maintenance plan to serve as a model for the preservation of other tombs.

The research that concludes that the brown spots on the tomb walls were probably the result of the tomb having been closed with wet paint led to the decision for the spots to be replicated in the facsimile. They are now understood as part of the story of Tutankhamen's burial, not the result of modern damage, and this has been quite correctly reflected in the facsimile.

Although the facsimile is fabricated from modern materials, which will be far more durable than Eighteenth Dynasty pigments and fixing agents, and will have many more visitors each year than the original, it will be interesting to see how it fares under such relaxed conditions. It cannot be used as a measure of how the original tombs will respond to the ongoing attentions of tourists, but analysis of the wear and tear may help conservators to refine their plans for tourist access to the original tombs.

The replica was officially unveiled in November 2012 in the Conrad Hotel in Cairo, at the opening of the EU Task Force Conference on Tourism and Flexible Investment in Egypt, to coincide with the 90th anniversary of the tomb’s discovery. The occasion was attended by hundreds of journalists, television cameras and photographers, and an absolute plethora of articles appeared on the subject in the media, accompanied by photographs of the original tomb (both from the 1920s and today) and the facsimile.

So, just how much of a facsimile is the facsimile?

|

| Figure 13. Scanning the painted surfaces of KV62 |

A combination of different devices were used to replicate the tomb, comprising three high resolution scanners, dedicated software, two cameras, a router and a flat-bed printer. Techniques used to complete the facsimile included rigorous colour matching and the merging, or “stitching” of 3-dimensional and colour data. Human intervention has been crucial in ensuring that the technology has produced not just a facsimile, but an equivalent experience.

|

| Figure 14. Swatches used to match the colours of the tomb to the facsimile |

The 3-D and photographic information was supplemented by research into the pigments, binders and techniques used to apply the decoration in the tomb, and the colours were calibrated manually to ensure that the visual experience equated to the original as it was recorded in 2009, complete with any of the changes that time has inflicted upon it. Colours were compared by means of hundreds of swatches to ensure that the colours in the facsimile corresponded exactly to those in the tomb under the same lighting conditions, thereby limiting the sense that “replicas inevitably depart from their prototypes in ambience” (Lowenthal 1985, p.291). A specially designed flat-bed inkjet printer was used to print the facsimile. Again, human intervention was required to ensure that the print-outs matched up with the colour samples.

The router, a type of drill that engraves surfaces to different levels depending on the data fed into it, was responsible for recreating the relief of the tomb’s surfaces on the polyurethane panels that make up the tombs walls.

|

Figure 15. Photograph and facsimile of the missing section |

But is a facsimile authentic?

It sounds as though the answer to that question would be quite straight forward, because how can a copy of something authentic be authentic itself? One’s instinctive response is to suggest that, whatever other benefits it might offer, a replica lacks authenticity. But this is not necessarily the case. Factum Arte does not dodge the question. When considering the role of facsimiles in Luxor, they observe that the facsimiles “are redefining the relationship between the original and the copy – re-negotiating the complex relationship between originality and authenticity” (Lowe and Macmillan Scott 2012, p.7). Authenticity is defined in different ways by different people. In the strictest sense, the definition by conservationist Michael Jones, is usefully rigorous:

"Authenticity involves preserving as much of the original as possible, as well as avoiding intrusive and sympathetic modern features such as arenas for sound and light or stage performances, electricity posts, such as those running through the middle of the main temple at Tanis, and even high-rise buildings overlooking an ancient site. It also includes protective measures that preserve authenticity and avoid invasive action: for example, walkways over original temple pavements to protect the stones, rather than replacing the worn-out slabs with mismatched modern stones."

Read it, Karnak, and weep. I still have the scar on one ankle from an unwelcome encounter with one of the sand-embedded flood-lights attached to the sound and light show at the temple.

So authenticity is at least partly about preservation of an original, however big or small, to maintain its integrity as something ancient. But the literal authenticity of the site itself is only a part of the story, because artefacts and sites are now research projects or tourist attractions, and have been perceived, understood and redefined in numerous ways, some of them bearing no relation to the original purpose of an object or site, often altering and even undermining the very idea of its authenticity. Lynn Meskell develops this theme: “The past is neither fixed nor complete, but open to a series of creative reworkings . . . . Encountering the silence of a long-dead civilization, we search in vain for memorable signs, desperately misreading them” (2004, p.184).

|

Figure 16. Walls and tourism in the Valley of the Kings |

The tombs were supposed to be sealed for eternity and hidden from view after the priests and family members had departed and workers had done their work to conceal the entrance from view, full of the items that were either stolen by tomb robbers or that found their way into museums. The owners of these sacred tombs would, in all probability, be horrified at the invasion of their afterlife homes, the removal of their contents. We do not experience these, or any other sites, in the way that their original owners intended, and our experience is therefore, by definition, inauthentic. Even those who claim to believe in the ancient Egyptian religion cannot experience it as people 3000 years ago did, when it was alive and well and forming a common language of understanding and belief. David Lowenthal, who sees the past as an artefact of the present, makes the point well:

“However faithfully we preserve, however authentically we restore, however deeply we immerse ourselves in bygone times, life back then was based on ways of being and believing incommensurable with our own. The past’s difference is, indeed, one of its charms: no-one would yearn for it if it merely replicated the present. But we cannot help but view and celebrate it through present day lenses” (1985, p.xvi).

However sympathetic we may be, we are interlopers from the future, and as David Lowenthal indicates, it is arguable that we cannot link to the past that we see before us in any way that would be recognized by those to whom the tomb was so important 3000 years ago.

|

Figure 17. Possibly the most famous image of ancient Egypt: The death mask of Tutankhamen |

The difficulties surrounding authenticity arise not with facsimiles and copies, but with interpretations. Eric Hornung’s 1999 book about how Egyptian spirituality has been re-interpreted and re-invented over the years is a lesson in itself about how the past can be reinterpreted in anything but authentic ways. More graphically, the famous Neolithic burial site of Newgrange in Ireland, with its beautifully carved stones and its opening to allow the sun to light the burial chamber on midsummer solstice, was excavated and restored from 1962 to 1975, and its exterior was rebuilt as an interpretation of what it might have looked like. This interpretation informs the minds of visitors and leaves them with the impression that they are looking at what was here in the past, when it may be nothing of the sort. Facsimiles, by contrast, do not interpret the past – that’s the job of archaeologists, visitor centres and museums. Facsimiles reproduce the present-day incarnation of the original as accurately as technically possible.

Then there’s the question of aura. Aura, a word defined by Cornelius Holtorf as “the form in which age and authenticity can supposedly be sensed from the object itself” (p.15 2005) incorporates the idea that a modern person receives a sense of something unique by looking at sites or objects from the distant past. Jaromir Malek refers to the same response as “frisson.” Although Michael Shanks believes that aura is an attribute of an object, not something that people bring to a site, the reality is probably nearer to David Lowenthal’s view that “[T]he felt past is a function of atmosphere as well as locale” (1985, p.240). Lynn Meskell ties the ideas of aura and authenticity together: “Authenticity is akin to the transmittable essence of a thing, including its substantive duration and its biographical history” (2004, p.182).

|

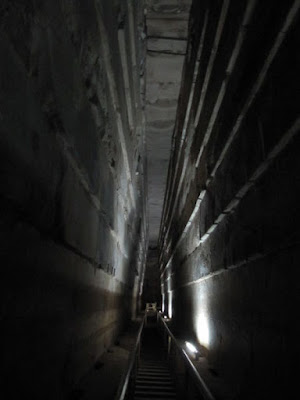

| Figure 18. The interior of the pyramid of Khufu at Giza |

As this example demonstrates and as Lowenthal’s above comment illustrates, aura is created, in part, by context. Anyone who has visited the pyramids of Giza with the image in mind of three vast and magnificent edifices rising out of empty desert will be disappointed. The approach to the pyramids is a bedlam of coach parks, camel rides, shops and western style restaurants at its edges, with a never-ending swirl of tourists, postcard, souvenir, camel- and horse-ride sellers and tourist police. Even behind the vast wall that separates the pyramids from Cairo, hawkers still plague visitors in spite of repeated promises that they will be ousted. Until you climb into the dimly lit pyramid and are overtaken by the sheer scale of the thing, there is precious little aura to be felt. At the Valley of the Kings the sense of antiquity is always overwhelmed by the sheer volume of tourists and their guides. And there are always heavy restrictions on where you can go and what you can see. Facsimiles offer a much less restrictive experience with greater freedom of movement, lower security and the revival of the site as it was in the past, before the infliction of modern damage and security precautions. Experiencing something old is not necessarily the same as experiencing something authentic, and often it doesn’t seem to matter. As Holtrof remarks (2005, p.119) “Intriguingly, some objects retain very strong aura even when it is openly stated that the actual material of which they consist is more recent.”

This point is perhaps made most clearly by two beautiful historic sailing ships, both preserved in dry dock. The Vasa, a warship built in Sweden in 1628, capsized and sunk in Stockholm harbour only minutes after launching, with a massive loss of life. Nearly perfectly preserved in the brackish waters in the still-used Stockholm harbour, she was raised in 1961. It was found that the waterlogged wood was one eighth water, and this had to be replaced by a chemical substance to maintain the structural integrity of the ship. So what we now see is at least one eighth modern materials. But somehow it doesn’t seem to matter, and the visitors to this astonishing vision and its surrounding visitor centre, myself included, seem completely unaffected by this unconcealed knowledge. Unlike the often depressing Giza plateau and the well trodden landscape of the Valley of the Kings, the Vasa remains evocative; it retains its aura.

|

| Figure 19. The Cutty Sark and the Vasa |

In all cases where ancient sites and objects have survived into the present day, we are still experiencing a later incarnation of the original site or object. As Adam Lowe commented recently: “Originality is not a state of being but a process. How objects are valued over time becomes part of the process.”

I suspect that what one takes away from a facsimile is very much a matter of personal attitude, and as such I will finish this section with a short personal comment about the World War I trench simulation in London’s Imperial War Museum. At the side of a gallery full of medals, uniforms, weapons, all of which are 100% authentic, there was a simulated First World War trench experience, complete with lighting, sound effects and some unpleasant surprises. This was no fairground attraction, and it succeeded in bringing wartime horrors to life for me in a way that the original museum pieces were unable to do. In this particular case, the simulation was, to me, much more powerful and gripping than the displays of historic items, as important and moving as they were. How authentic the effect was is impossible to say without speaking to someone who both survived the trenches and experienced the exhibit, but it certainly pushed me nearer to an appreciation of that particular past than I had before I visited.

Whether the authenticity or aura of a site is retained at the site depends to an enormous extent on how it is experienced. Some original sites have lost both their sense of authenticity and their aura, whereas their replicas offer a much greater sense of what the original was like. What you get out of a simulation, copy or facsimile depends partly on what you bring to it. A sense of curiosity and the willingness to accept a facsimile as a facsimile, together with the knowledge that by accepting something new, the ancient marvel that it replaces will be preserved, should be enough for most of us.

For a short time it is hoped that KV62 and the facsimile will be open together, allowing both scholars and the public to compare for themselves the original site and the facsimile, enabling them to judge for themselves the authenticity of the replacement.

Will the facsimile attract visitors?

|

| Figure 20. The KV62 facsimile |

This question is tied in closely to the previous section’s discussion of whether experiencing the original actually matters. All the available evidence argues that the answer is probably that it will indeed attract paying visitors. Factum Arte themselves believe that attitudes towards the value of replicas has taken at least ten years to change, with the idea of facsimiles producing “a reaction of scorn from the cultural elite and a sense of being cheated from the public” (Lowe and Macmillan Scott 2012, p.14). But they and other writers have observed a significant change in attitude in the last decade, with the public and scholars alike valuing the role of facsimiles in reuniting the public with equivalent experiences in the vicinity of the original sites.

Michael Jones believes that replicas in Egypt have been rejected to date for financial reasons, but he, like many others, points to the successes of Altamira and Lascaux and believes that they may well offer the best opportunity for the preservation of the royal tombs. Helen Nicholson in The Daily Mail says that when Lascaux II was opened some 20 years ago, it was a great attraction. Today, the number of visitors to the new cave has risen from 100,000 visitors 20 years ago to over 250,000 per year, with about 5 million visitors recorded in total since Lascaux II opened. At Altamira, where the old museum of 60,000 square metres has been expanded to 160,000 square metres, more than 200,000 visitors were recorded at the Neocueva between 19th July until 30th December 2001. Perhaps more relevant to the Tutankhamen facsimile, Factum Arte’s copy of the burial-chamber of Tuthmosis III, unveiled in 2003, has already had more than 3 million visitors during its tour with the exhibition The Quest for Immortality: Treasures of Ancient Egypt.

Replicas seem to be successful, and the public appears to understand why they are necessary. They are not a matter of trying to fool people but of trying to involve them in heritage management by given them an altogether richer experience, with closer and unlimited access to something that far more closely resembles the site that was last seen by the people who created and used it. It seems likely that people who want to get a feeling for what sort of space was filled by the staggering number of objects will still want to visit and experience the size of the tomb and view the replica paintings, seeing facsimiles not as fakes but opportunities.

Speaking for myself, a replica of the tomb of Horemheb in the Valley of the Kings would be superb – I have never seen it and have always wanted to see the fragments provided by photographs in books presented as they were supposed to be seen. Of course it would be nice to see the original, but I respect the reason for the tomb’s closure and an exact facsimile would do me just as well from the point of view of visualizing and feeling how the tomb was put together and experiencing how the paintings were organized into a comprehensible narrative. And I will be amongst the first in line to see the replica of the tomb of Seti I. As Troy Lovata puts it (2007, p.17), visitors are “savvy enough to know that inauthentic objects can convey authentic ideas”.

It is hoped that the tomb will be accompanied by a visitor centre to provide information about the tomb’s owner, its history, the discovery and its wider context. At the same time, one of the good things about the replica is that it will allow visitors to interact with the tomb directly, to form their own impressions.

When and where will the facsimile be located?

|

Figure 21. Repeated checking of the colours that were used to create the facsimile |

The ongoing Getty Conservation Institute conservation project findings have yet to be released, but may provide a clearer view on the fate of the tomb. Hopefully a decision about when and where the location for the facsimile will be made long before KV62 closes and its replacement needed. When the idea of replicas was first discussed in Egypt, it was suggested that they might be located in Cairo, which seemed a little inappropriate given that tourists visiting the Valley of the Kings might reasonably expect their Kings Valley experience to be located in the vicinity of the other tombs, but this idea seems to have been abandoned, at least for the present. In 2010 the Supreme Council of Antiquities proposed to install it near to Howard Carter’s Dig House at the entrance to the Valley of the Kings, but the present Minister of State for Antiquities, Mohamed Ibrahim, has said that it is unlikely that this will now be the location. Although the Factum Arte report states quite clearly that it was a condition that the facsimile should be on Luxor’s West Bank, so that “it benefits the Valley of the Kings and provides work for people on Luxor’s West Bank” (Lowe and Macmillan Scott 2012, p.13), Minister of Antiquities Mohamed Ibrahim is quoted in the Daily News Egypt saying that it might be located instead in Sharm el Sheikh or Hurghada as an advert for the Valley of the Kings (Heine 2012). Removing it so far from its context might well deprive it from much of its sense of authenticity, and seems a terrible shame.

Weighing nearly four tons, the facsimile will be stored in the European Union embassy in Cairo until it is needed. It remains unclear exactly when and where it will be installed.

Future plans

For the immediate future, Factum Arte are hoping that the recorded data will be readily available to the public on a Creative Commons licence, but they emphasise that all copyright and commercial benefits will belong to the Supreme Council of Antiquities. How accessible the images will be to the public and to publications wishing to use them to illustrate articles has not yet been made clear.

Already the Factum Foundation website offers a high resolution image navigator to enable people to explore the tomb of Tutankhamen. It is an interactive Flash-based viewer application developed for the Supreme Council of Antiquities and other specialists for studying and monitoring the tomb, and this will be developed to permit users to move around the tomb, zooming in on areas of particular interest.

A measure of the confidence that both Egypt and the facsimile builders have in the product lies in the fact that the same company is expected to begin working on replicas of the tombs of Seti I and Queen Nefertari, which have both been closed to the general public for over a decade. Both tombs are much larger than that of Tutankhamen. The intention is for Factum Arte to train Egyptian specialists to do much of the work, based at custom-built workshops to be located in Luxor, so that the local community can benefit. The projects should take around five years to complete.

|

| Figure 22. A fragment from the tomb of Seti I in the British Museum, London |

The tomb of Nefertari, which underwent major conservation and restoration by the Getty Conservation Institute during the 1980s should be less difficult than that of Seti I, but will still represent a challenge. The painted surfaces cover an area of 900 square metres, a much smaller area than that of Seti I, but considerably larger than KV62 and with considerably more paintwork than the smaller tomb.

It is planned that the work to record both tombs and the building of the new facsimiles will be carried out by a Luxor-based Egyptian team who will be trained by the Factum Arte specialists. Workshops will be set up in Luxor to serve as local bases. A new scanner, the Lucida, has been developed specially for these projects, so that the high-relief of the surfaces can be captured accurately. Both facsimiles should be very welcome additions for visitors who might otherwise have to forgo the experience of all three tombs entirely. Both Factum Foundation and the Society of Friends of the Royal Tombs of Egypt are committed to raising the funding from private and public bodies, which will amount to some 20 million Euros.

Conclusions

|

| Figure 23. Working on the replica |

Whether tourists will appreciate the alternative remains to be seen, but the replica will certainly offer them an ongoing opportunity to imagine the treasures from the tomb, now kept in the Cairo Museum, into something like their original context. And Factum Arte found that most of the tourists who asked questions while their team was carrying out survey work were pleased that a solution was being found, and were happy to sacrifice the experience of the original for that of an exact copy. Hopefully tourists will be glad to become part of the solution, rather than the cause of the problem, enjoying both the sense of responsibility and the artwork in the facsimile. As Mike Pitts said, writing about the facsimile, “Heritage tourism may be good for economies but, badly managed, it harms the heritage. It’s right that our access should be controlled” (Pitts 2011).

The Valley of the Kings Site Management Masterplan put forward by Kent Weeks and Nigel Hetherington is already being actioned. The Getty Conservation Institute’s five year project should be completed in 2014. At this time all the information gathered by the team should be synthesized and the GCI’s conservation plan and other recommendations should be ready to present to the SCA. It is thought that treatment of the tomb, sarcophagus and the gilded coffin will then take an additional two years to complete. As part of the project, a monitoring and maintenance program will be devised and visitor carrying capacity will be assessed, resulting in a visitation policy which will incorporate visitor numbers, lighting, ventilation, and commercial uses including filming and photography. The Tutankhamen project will, it is hoped, provide a case study, which will form the model for further conservation work in the area. It is intended that the income from ticket sales to the facsimile will be used, at least in part, to conserve and maintain KV62, securing its future as far as possible and it is hoped that under these conditions serious researchers will still be able to access the original tomb if their research requires it.

Regarding the very welcome facsimile of the tomb of Tutankhamen, I’ll leave the final word with Mike Pitts: “No, it’s not the real tomb. But it is a real facsimile, and when you visit you will become part of a cutting-edge research project. Before, you were just a pan-scourer” (Pitts 2011).

|

| Figure 24. The facsimile in the making |

|

Figure 25. The Factum Arte replica, ready for display to the public |

Image Credits

Figures 1, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 21, 22, 23, 24 and 25 are used with kind permission of Factum Arte (http://www.factum-arte.com), which retains the copyright on all images.

Figures 5, 19a (Cutty Sark) and 21 by Andrea Byrnes

Figure 2 by Josh D. Boz (Public Domain)

Figure 3 by Harry Burton (Public Domain)

Figure 4 by MarkH (Public Domain)

Figure 7 by Prof Saxx (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license)

Figure 9 from the Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911 (Public Domain).

Figure 16 by Kounosu (This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic license)

Figure 17 by Jon Bodsworth (Public Domain)

Figure 18 by Popo le Chien (Public Domain)

Figure 19b (The Vasa) by Georg Dembowski (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license)

References

Almagro Basch, M., Presedo Velo, F., del Carmen Pérez Díe, M., Almagro Gorbea, M-J. 1978

La Tumba de Nefertari. Monografías Arequelógicas No.4. Museo Arqueólogico Nacional

Beach, Alistair 2012. How tourism cursed tomb of King Tut. The Independent, 4th November 2012

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/how-tourism-cursed-tomb-of-king-tut-8280603.html

Carter, H. and Mace, A.C. 1977 (1923). The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun. Dover Publications

Cohen, Jennie 2011. Was King Tut Buried in a Hurry?. History.com

http://www.history.com/news/was-king-tut-buried-in-a-hurry

Corzo, M-A. (ed) and Afshar, M. 1993. Art and Eternity: Nefertari Wall Paintings Conservation Project 1986-1992. Getty Conservation Institute

David, R. 2000. The Experience of Ancient Egypt. Routledge

Dowson, T. 2012. Lascaux – International Exhibition to Travel the World

Archaeology Travel.

http://archaeology-travel.com/exhibitions/lascaux-international-exhibition-to-travel-the-world/

De Las Heras, C., Lasheras, J.A., Sanchez-Moral, S., Bedoya, J., Cañaveras, J-C., and Soler, V. 2004

The Preservation of the Cave of Altamira (1880-2002) In ed. Le Secretariat du Congrès. Section 18: Muséographie et Société contemporaine. Actes du XIVème Congres UISPP, Univesité de Liège, Belgique, 2-8 Septembre 2001

BAR International Series 1313

The Economist 2012. Toot toot, King Tut: Technology in the service of history. November 10th 2012

El-Aref, Nevine 2012. Tutankhamun’s replica tomb unveiled. Al Ahram Weekly, Tuesday 13 Nov 2012. http://bit.ly/PRkI2i

Factum Arte 2012. http://www.factum-arte.com/eng/default.asp

Factum Arte: Work on the Facsimile of Tutankhamun

http://www.factum-arte.com/eng/conservacion/tutankhamun/tutankhamun_en.asp

Conservation and Documentation of Cultural Heritage http://www.factum-arte.com/eng/conservation.asp

Factum Arte: The Last Supper http://www.factum-arte.com/eng/artistas/greenaway/leonardo_milan.asp

Factum Arte: Facsimile of a section of the burial chamber from the tomb of Seti I

http://www.factum-arte.com/eng/conservacion/seti/seti_en.asp

The Factum Foundation http://www.factumfoundation.org

Factum Foundation high resolution image navigator

www.factumfoundation.org/tut-browser.php

www.highres.factum-arte.org/Tutankhamun

Fagan, Brian 2004. The Rape of the Nile. Tomb robbers, tourists and archaeologists in Egypt

Westview Pres.

Frayling, C. 1992. The Face of Tutankhamun. Faber and Faber

The Getty Conservation Institute 2009-2010. Conservation and Management of the Tomb of Tutankhamen. http://www.getty.edu/conservation/our_projects/field_projects/tut/index.html

In the Valley of the Queens (video)

http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/videos/valleyqueens.html

González, V.G. and Ibánez, M.A.I.O. Conociendo a nuestros visitantes. Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira. Ministerio de Cultura

Heine, Adel 2012 Preserving the past by recreating it: Tutankhamun’s tomb facsimile arrives in Egypt. Daily News Egypt. http://dailynewsegypt.com/2012/11/15/preserving-the-past-by-recreating-it/

Hetherington, N.J. 2009. An Assessment of the Role of Archaeological Site Management in the Valley of the Kings, Luxor, Egypt. In Hassan, F.A., Tassie, G.J., De Trafford, A., Owens, L., and van Wetering, J. Managing Egypt’s Cultural Heritage. ECHO

Hodder, I. 1999. The Archaeological Process. John Wiley and Sons

Holtorf, C. 2005. From Stonehenge to Las Vegas. Archaeology as Popular Culture. Altamira Press

Hornung, E. 1999. The Secret Lore of Egypt. Its Impact on the West. Translated from the German by

David Lorton. Cornell University Press

International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). Charters and other doctrinal texts

http://www.icomos.org/en/charters-and-other-doctrinal-texts

Jones, Michael 2008. Monument and Site Conservation. In Wilkinson, R. H. Egyptology Today

Cambridge University Press

Insoll, T. 2007. Archaeology. The Conceptual Challenge. Duckworth

Kleingardt, B. 1968. Wasa Statens Sjöhistoriska Museum

Lasheras, Jose A. and de las Heras, Carmen 2006. Cueva de Altamira and the preservation of its Palaeolithic art. Coalition No. 12, July 2006, Special Issue: Conservation of Rock Art p.7-13

CSIC Thematic Network on Cultural Heritage

Lowe, Adam and Macmillan Scott, M. John 2012. The authorized facsimile of the burial chamber of Tutankhamun. With sarcophagus, sarcophagus lid and the missing segment from the south wall

http://www.factum-arte.com/publications_PDF/tutankhamun_90anniversary.pdf

Lowenthal, D. 1985. The Past is a Foreign Country. Cambridge University Press

Lovata, Troy 2007. Inauthentic Archaeologies. Public Uses and Abuses of the Past. Left Coast Pres

Malek, Jaromir 2009. Some thoughts inspired by a current exhibition: ‘Tutankhamun: His Tomb and Treasures.’ Brno, Titanic Hall, Herspická 9, October 16, 2008 – March 15, 2009

http://www.tut-ausstellung.com/downloads/tut_press_jaromir_malek_en.pdf

http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gri/4semmel.html

McDonald, John K. 1996. House of Eternity – The Tomb of Nefertari. Thames and Hudson

McLane, J. and Wüst, R. 2000. Flood hazards and protection measures in the Valley of the Kings

Cultural Resource Management 23, 6 (2000), p.35-36

Meskell, L. 2004. Object Worlds in Ancient Egypt. Material Biographies Past and Present. Berg

Patronato del Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, Gabinete de Prensa. Aprobado el Programa de Investigación para la Conservación Preventiva y Régimen de Acceso de la Cueva de Altamira

http://museodealtamira.mcu.es/web/docs/Comunicado_MECD.pdf

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. 2002. Backgrounder on the Burial Chamber of Thutmose III. http://www.nga.gov/press/exh/188/background.shtm

Nicholson, Helen 2012. A facsmilie fit for a Pharaoh: replica of Tutankamun’s tomb unveiled in Egypt. Daily Mail 14th November 2012. http://bit.ly/TINrUY

O’Kelly, M.J. 1982. Newgrange. Archaeology, art and legend. Thames and Hudson

Pendelbury, J. 2009. Conservation in the Age of Concensus

Pitts, M. 2011. Your last chance to see Tutankhamun’s tomb. The Guardian, January 17th 2011

http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2011/jan/17/tutankhamun-tomb-to-close

Reeves, Nicholas 1990. The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. Thames and Hudson

Sedky, A. 2005. The Politics of Conservation in Cairo. International Journal of Heritage Studies 11, No.2, May 2005 p.113-30

Shanks, M. 1988. The life of an artefact in an interpretative archaeology. Fennoscandia Archaeologica 15, p.15-30

Society of the Friends of the Royal Tombs of Egypt (SFRTE). www.sfrte.ch

Shanks, M. 1991. Experiencing the Past: On the Character of Archaeology. Routledge

Smiles, S. and Moser, S. 2004. Envisioning the Past: Archaeology and the Image. Wiley Blackwell

Supreme Council of Antiquities. Press Release – Tomb of Tutankhamun Conservation Project

http://www.drhawass.com/blog/press-release-tomb-tutankhamen-conservation-project

Tilley, C. 1993. Interpretation and a poetics of the past. In Tilley, C. (ed.), Interpretative Archaeology, p.1-26. Berg

Tung, A.M. 2001.Preserving the World’s Great Cities, the Destruction and Renewal of the Historic Metropolis. New York

Tutankhamun – His Tomb and his Treasures (exhibition). http://www.tut-ausstellung.com/en/deutschland/the-great-tutanchamun-must-see-exhibition.html

Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of Pharaohs (exhibition). http://events.nationalgeographic.com/events/exhibits/king-tut-golden-age/

Tutankhamun – The Golden Beyond (exhibition). http://news.nationalgeographic.co.uk/news/2004/11/photogalleries/king_tut/

Tutankhamun – The Golden King and the Great Pharaohs (exhibition). http://www.kingtut.org/

Tyldesley, J. 2012. Tutankhamen’s Curse. The developing history of an Egyptian King.

Profile Books

Weeks, K.R and Hetherington, N.J. 2006. The Valley of the Kings Site Management Masterplan

Theban Mapping Project, Cairo, Egypt. http://www.thebanmappingproject.com/about/masterplan.html

World Monuments Fund http://www.wmf.org.uk/

Originally published in Egyptological Magazine, Edition 8, April 18th 2013.

Comments